4

Followers

8

Following

Breadcrumb Reads

This is the companion blog to my main book blog, Breadcrumb Reads. My reading tastes veer towards the classics, literary fiction, creative non-fiction and historical fiction.

Finding God in Unexpected Places

This wasn't what I thought it would be considering the title. I think I was expecting a sort of analysis/guide book of sorts. It turned out to be a collection of Yancey's articles over the years. While many, for the most part, were dry and didn't give me anything or much to glean from, there were a few gems within. Having read this about two months ago and not having this book at hand right now, I cannot really pin-point the articles.

This wasn't what I thought it would be considering the title. I think I was expecting a sort of analysis/guide book of sorts. It turned out to be a collection of Yancey's articles over the years. While many, for the most part, were dry and didn't give me anything or much to glean from, there were a few gems within. Having read this about two months ago and not having this book at hand right now, I cannot really pin-point the articles. However, I do like how Yancey has pointed out God in every place and in every situation. Most often when we wonder if God is really there, and why He is silent, He is actually working His most! Inspiring. :)

Until this last read Pride and Pregudice ranked 5 stars in my list. However, I seem to have lost it one star after this read for the following reason(s).

Until this last read Pride and Pregudice ranked 5 stars in my list. However, I seem to have lost it one star after this read for the following reason(s).I found it a bit slow going this time around. Perhaps this was because I was in danger of going through a reading slump at the time. But mostly, for me, I found the Elizabeth-Darcy romance did not charm me as much as it used to. Not to mention that I found I didn't really care for Elizabeth as well as her father -- the one was too opinionated for my tastes and the other too flippant about everything. I, however, did find myself liking and respecting Jane a lot more (and Bingley as well). I have a feeling that my fifth time round of reading this book was influenced by my read of Sense and Sensibility only a few months previously. Having enjoyed the character of Elinor a great deal, I found much of her in Jane. And while I did not dislike Marianne, I found that what could be acceptable in a 17 year old, was simply annoying and irritating in a twenty-something year old a.k.a Elizabeth.

My reaction to the rest of the characters in the story were pretty much the same as before.

Where this particular novel once ranked among my favourites, I find it now having it's place only after Sense and Sensibility, Persuasion and Northanger Abbey!

Read this book again after about 12 years!

Read this book again after about 12 years! It was fun. Reminded me as to why I began getting into this series!:D

The "Da Vinci Code": A Response

I've read these details of overwhelming evidence of the books of the bible, especially as those concerning the gospels and epistles, many times before. As always, it would seem, any suggestion to the contrary hold no weight at all, lacking even a single shred of proof.

I've read these details of overwhelming evidence of the books of the bible, especially as those concerning the gospels and epistles, many times before. As always, it would seem, any suggestion to the contrary hold no weight at all, lacking even a single shred of proof. In is short book Gimbel seeks to refute the claims made in The Da Vinci Code regarding the documents that apparently prove Jesus was married and that Emperor Constantine was the one who suggested the deity of Jesus in order to control the masses.

While reading this book I could see why it is considered one of the top 50 ground-breaking Christian books. John Stott writes powerfully and convincingly, steadily breaking down the major components of Christianity individually before putting them all together as a whole. He begins by making it clear that the living God is one who "takes the initiative, rises from his throne, lays aside his glory, and stoops to seek until he finds" man who is "still lost in darkness and sunk in sin". He very simply brings out the kind of relationship God and man were supposed to have that was broken because of sin, and how Jesus Christ is the link that bridges the gap between God and man, allowing for the relationship they once had with each other.

While reading this book I could see why it is considered one of the top 50 ground-breaking Christian books. John Stott writes powerfully and convincingly, steadily breaking down the major components of Christianity individually before putting them all together as a whole. He begins by making it clear that the living God is one who "takes the initiative, rises from his throne, lays aside his glory, and stoops to seek until he finds" man who is "still lost in darkness and sunk in sin". He very simply brings out the kind of relationship God and man were supposed to have that was broken because of sin, and how Jesus Christ is the link that bridges the gap between God and man, allowing for the relationship they once had with each other. While all of the above and much more of what he says were already clear to me, it was lovely reading it all out in print, and so simply and clearly stated. I also learnt a few other things in the final chapters that serve as what-to-dos and as encouragement for those who yearn to walk with Christ.

When I decided to read Louisa May Alcott’s Behind a Mask for Transcendentalist Month, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. The brief blurb claimed it was so unlike the usual Alcott-fare most people are familiar with — the likes of Little Women, Eight Cousins and An Old-Fashioned Girl. Apparently it was to be dark and mysterious…the kind of material that no one, not knowing Alcott except through her well-known works, would ever have suspected. The story is this. A young woman comes to the Coventrys as a governess, highly recommended by a family friend of theirs. However, she brings with her a mystery, a love affair everyone suspects she had with the elder son of this friend. Being a meek and lovely woman, though, more than half the family grows to love her. But the elder Mr Coventry is not convinced that Jean Muir is an innocent. He is quite sure she has ambitious designs, and we are very speedily assured that Coventry is right. The rest of the novella charters the course of Jean Muir’s plan to captivate the Coventry boys and the rest of the household.

When I decided to read Louisa May Alcott’s Behind a Mask for Transcendentalist Month, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. The brief blurb claimed it was so unlike the usual Alcott-fare most people are familiar with — the likes of Little Women, Eight Cousins and An Old-Fashioned Girl. Apparently it was to be dark and mysterious…the kind of material that no one, not knowing Alcott except through her well-known works, would ever have suspected. The story is this. A young woman comes to the Coventrys as a governess, highly recommended by a family friend of theirs. However, she brings with her a mystery, a love affair everyone suspects she had with the elder son of this friend. Being a meek and lovely woman, though, more than half the family grows to love her. But the elder Mr Coventry is not convinced that Jean Muir is an innocent. He is quite sure she has ambitious designs, and we are very speedily assured that Coventry is right. The rest of the novella charters the course of Jean Muir’s plan to captivate the Coventry boys and the rest of the household.When I began reading this story I was fascinated, because almost from the start we are given to understand that Jean Muir is not all that she seems to be. The hint is subtle but there:

Poverty seemed to have set its bond stamp upon her, and life to have had for her more frost than sunshine. But something in the lines of the mouth betrayed strength, and the clear, low voice had a curious mixture of command and entreaty in its varying tones. Not an attractive woman, yet not an ordinary one; and, as she sat there with her delicate hands lying in her lap, her head bent, and a bitter look on her thin face, she was more interesting than many a blithe and blooming girl.

A few paragraphs later we are made privy to the woman behind the mask. Not as young as she appears before the family, dark-haired as opposed to her fair wig, a face puckered with hatred and bitterness in sharp contrast with her mild, meek and gentle appearance — the effect is stunning. Really, I could not help but admire how such a woman could be the pretty governess she makes everyone believe she is. This side of her struck some sense of fear as to how diabolical her plans really were. I can’t say that I was for her throughout the story…neither can I say that I was particularly against her. But, at the end of it all, when I thought about it, I figured Alcott was really trying to say something. That the Victorian woman, for the most part, was only putting on a face to satisfy her patriarchal society. Jean Muir appears to us in the guise of what is expected of a woman…and in her case, not just as a woman, but as one from her lowly station. It is interesting to note how Muir rises in the esteem of her employers when they believe her to be an impoverished woman of genteel birth. I think it also significant that Muir wears a blond wig to cover up her dark hair. This did not convey anything to me besides the fact that fair hair was considered, not only beautiful, but angelic in that society.

[...]

I was reminded of dark-haired and passionate Jo March, and now here was Jean Muir, a perhaps darker side of Alcott, representing, not just her natural looks, but also the fire within her. I believe Alcott was echoeing something that Wollstonecraft says in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman — that if one does not allow a woman to be educated, she is bound to resort to wiles in order to get her own way, for she is not allowed to do it honestly and openly. Jean Muir is an ambitious young woman, and perhaps it is most natural for her to want to better her situation in life. While courses are open for men to do so, the only way open to the likes of Muir is to capture the interest and attention of a rich son in the household she works for. One cannot, then, blame Muir for the tactics she resorts to. She must live. She fears continual poverty. Society will allow her no other means to grow. So, she chooses to take the course of deceit over dying in poverty. --> to read read the rest of this analysis click on the link.

I owned a copy of Alice in Wonderland a long time ago as a child. I recall picking it up several times, but always giving when Alice comes to the table with the golden key and shrinks. I think, even as a child, I felt it was too unbelievable. Or maybe I just didn't care for Alice at all. I couldn't relate to her. Whatever the reasons might have been, this book lay in shelf for so long until I gave it away about ten years ago without having read it at all.

I owned a copy of Alice in Wonderland a long time ago as a child. I recall picking it up several times, but always giving when Alice comes to the table with the golden key and shrinks. I think, even as a child, I felt it was too unbelievable. Or maybe I just didn't care for Alice at all. I couldn't relate to her. Whatever the reasons might have been, this book lay in shelf for so long until I gave it away about ten years ago without having read it at all.However, as one grows older one does feel guilty for not have given 'must reads' a proper chance. So, it's been a little while since I'd been planning on getting myself an other copy of Lewis Carroll's famous book. Never really getting round to buying though, I decided to read it in installments from DailyLit.

I'm glad I did. I still found Alice annoying. All the little animals were interesting. But, what really captured my attention this time and caused to really like this books was Carroll's play with words. He would take words, exploring their various meanings within the context of the story. I suppose that is why, at a cursory glance, the story itself is meaningless. But, stay awhile and let the sounds wash over you without letting the story bother you, and it's quite fascinating! Even Carroll's own twists on well known rhymes and poems make sense in this topsy turvy world.

My favourite chapter was "The Mock Turtle's Story". It was the one in which I enjoyed the play of words the most!

`When we were little,' the Mock Turtle went on at last, more calmly, though still sobbing a little now and then, `we went to school in the sea. The master was an old Turtle--we used to call him Tortoise--'

`Why did you call him Tortoise, if he wasn't one?' Alice asked.

`We called him Tortoise because he taught us,' said the Mock Turtle angrily: `really you are very dull!'

`You ought to be ashamed of yourself for asking such a simple question,' added the Gryphon; and then they both sat silent and looked at poor Alice, who felt ready to sink into the earth. At last the Gryphon said to the Mock Turtle, `Drive on, old fellow! Don't be all day about it!' and he went on in these words:

`Yes, we went to school in the sea, though you mayn't believe it--'

`I never said I didn't!' interrupted Alice.

`You did,' said the Mock Turtle.

`Hold your tongue!' added the Gryphon, before Alice could speak again. The Mock Turtle went on.

`We had the best of educations--in fact, we went to school every day--'

`I'VE been to a day-school, too,' said Alice; `you needn't be so proud as all that.'

`With extras?' asked the Mock Turtle a little anxiously.

`Yes,' said Alice, `we learned French and music.'

`And washing?' said the Mock Turtle.

`Certainly not!' said Alice indignantly.

`Ah! then yours wasn't a really good school,' said the Mock Turtle in a tone of great relief. `Now at OURS they had at the end of the bill, "French, music, AND WASHING--extra."'

`You couldn't have wanted it much,' said Alice; `living at the bottom of the sea.'

`I couldn't afford to learn it.' said the Mock Turtle with a sigh. `I only took the regular course.'

`What was that?' inquired Alice.

`Reeling and Writhing, of course, to begin with,' the Mock Turtle replied; `and then the different branches of Arithmetic-- Ambition, Distraction, Uglification, and Derision.'

`I never heard of "Uglification,"' Alice ventured to say. `What is it?'

The Gryphon lifted up both its paws in surprise. `What! Never heard of uglifying!' it exclaimed. `You know what to beautify is, I suppose?'

`Yes,' said Alice doubtfully: `it means--to--make--anything--prettier.'

`Well, then,' the Gryphon went on, `if you don't know what to uglify is, you ARE a simpleton.'

Alice did not feel encouraged to ask any more questions about it, so she turned to the Mock Turtle, and said `What else had you to learn?'

`Well, there was Mystery,' the Mock Turtle replied, counting off the subjects on his flappers, `--Mystery, ancient and modern, with Seaography: then Drawling--the Drawling-master was an old conger-eel, that used to come once a week: HE taught us Drawling, Stretching, and Fainting in Coils.'

`What was THAT like?' said Alice.

`Well, I can't show it you myself,' the Mock Turtle said: `I'm too stiff. And the Gryphon never learnt it.'

`Hadn't time,' said the Gryphon: `I went to the Classics master, though. He was an old crab, HE was.'

`I never went to him,' the Mock Turtle said with a sigh: `he taught Laughing and Grief, they used to say.'

`So he did, so he did,' said the Gryphon, sighing in his turn; and both creatures hid their faces in their paws.

I read this passage over and over again and laughed myself to stitches! Carroll is simply wonderful twisting words and sounds here. If I were to read Alice in Wonderland again, I would do so to read Carroll's language and not for the story in particular.

Hmmm...really, now that I think about it I would give this book a 4 on 5 rating rather than the 3 it has now. I'm off to change that!

When I was first approached by Paul McDonnold to read and review The Economics of Ego Surplus, I was curious. For one, I had never heard of an economics thriller before. Two, I thought it would be interesting to read a piece of fiction with economics as its central theme. While I have no particular interest in the subject of economics, I do respect it, especially as I hear a great deal about it from my father who is an expert on all things to do with economics. McDonnold allowed me a glimpse of his novel before I decided I would like to read it. That ten-page glimpse got me quite excited to read further for there was something so very Ayn Rand-ish about it. There was a sense of something huge to come, and with all the power that seemed to exist in that one room of the first scene, I simply couldn't wait to start.

When I was first approached by Paul McDonnold to read and review The Economics of Ego Surplus, I was curious. For one, I had never heard of an economics thriller before. Two, I thought it would be interesting to read a piece of fiction with economics as its central theme. While I have no particular interest in the subject of economics, I do respect it, especially as I hear a great deal about it from my father who is an expert on all things to do with economics. McDonnold allowed me a glimpse of his novel before I decided I would like to read it. That ten-page glimpse got me quite excited to read further for there was something so very Ayn Rand-ish about it. There was a sense of something huge to come, and with all the power that seemed to exist in that one room of the first scene, I simply couldn't wait to start.Before I go any further into my thoughts about and reactions to this book let me brief you in on the story. There is a terrorist plot afoot. But this time it has nothing to do with bombings or gunnings. Instead, the U.S. stock market is being threatened. Kyle Linwood is called in to help discover how exactly the terrorists plan on having the market crash on such a large scale. Linwood goes from point to point or rather, person to person before he is able to understand how such a thing can happen. Obviously, whoever is planning this has to have solid financially backing or be financially sound. The trail leads him and the FBI agent, Marshall, to the opulent city of Dubai where they finally nab the terrorists.

Now, I am not sure if my expectations were too high, but I had a problem with this novel on two levels. In theory, the story sounds fascinating. But as the plot unfolds its 'thriller' quotient is almost non-existent. The reason why Linwood, a mere graduate student, is called in to help with the investigation was rather flimsy. At the end his part was to collect data on the possibility of the market crashing on a large scale – something that an expert economist, or the couple of them mentioned in this book, could have provided the FBI with had they asked. Then there was the whole case with an assassin and finally the terrorists themselves – everything was simply too easy…too convenient.

However, keeping in mind the fact that when McDonnold asked me if I could review his novel he said, “…The Economics of Ego Surplus…helps the reader understand how the global economy works while being entertained” I think perhaps he has succeeded in that respect. Through Linwood McDonnold shows us how economics is not some scholarly, unreachable subject, but something that every single person has dealings with in their everyday activities. He breaks economics down in to everyday living making it easy to understand certain concepts, especially in relation to the rise and fall of the stock market and the part both the government and the layman play in it. Again, I was not convinced at the way all these concepts were delivered in terms of moving the plot along, but the concepts stay with you.

To summarise, while I would not rate this novel as a good thriller, I would recommend it as a good way to get beginners interested in economics. Therefore, as a thriller I would give it a mere 2/5 but as an introduction to economics while being entertaining I would give it a 4/5.

Forbidden Mind (Forbidden, #1)

I got a kindle version of this novel(la) from Smashwords when I found it was going free for a few days. What grabbed my attention about this book was its whole X-men-like theme (I love the X-men!). The premise is this - A school, nicknamed Rent-A-Kid, educates and trains children with paranormal powers. These kids and their powers are leant out to the highest bidder who needs to dig up dirt or take revenge on someone. But, when these kids turn eighteen they are allowed to "retire" and pursue their own lives. Sam is about to turn eighteen and she's looking forward to a 'normal' life in college when all of a sudden her entire life turns upside down on her first meeting with a new-comer into Rent-a-Kid. The rest of the book is a question of whether or not Sam and her friends will survive what they know.

I got a kindle version of this novel(la) from Smashwords when I found it was going free for a few days. What grabbed my attention about this book was its whole X-men-like theme (I love the X-men!). The premise is this - A school, nicknamed Rent-A-Kid, educates and trains children with paranormal powers. These kids and their powers are leant out to the highest bidder who needs to dig up dirt or take revenge on someone. But, when these kids turn eighteen they are allowed to "retire" and pursue their own lives. Sam is about to turn eighteen and she's looking forward to a 'normal' life in college when all of a sudden her entire life turns upside down on her first meeting with a new-comer into Rent-a-Kid. The rest of the book is a question of whether or not Sam and her friends will survive what they know. Right from beginning to the end this book is fast paced. No words are wasted. The writer has a plan and she does not deviate a single bit. Things happen so fast you find yourself at the edge of your seat all the time! If I were looking for another book to compare this style of story-telling to, I would pick Rick Riordan's Percy Jackson series. This novel does not pretend to be anything that it is not. If you're looking for some racy adventure, with so many things happening so quickly together; if you're looking for something that is nail-bitingly exciting and refuses to drag its feet, then this book is worth a read.

Simply put, it is exciting!

The last time I felt this way was when I read Gone With the Wind, and now, as I turned the final pages of The Ladies of Grace Adieu and other stories - sheer disappointment that there was no more to read. I've had such a lovely five days exploring and re-exploring, in some cases, the magical world that Susanna Clarke has built. For those of you who are unaware of this author, she made a debut a few years ago with her faerie novel, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. It is set in Regency England where magic is a highly scholarly field with only two gentlemen (the ones whose names make up the title) really practicing it. Clarke brilliantly weaves magic mixed with many real political issues of the day, especially the battles with Napoleon Bonaparte. Clarke recreates the original meaning of 'faerie'. It isn't happy and pleasant; it is eerie and unnerving sometimes. It's the kind of stuff country folk must've talked about in fearful and hushed tones when the moon was up and they gathered round the warm fires of their humble homes. The kind that they used most effectively to describe strange things that happened around them that they could not otherwise explain.

The last time I felt this way was when I read Gone With the Wind, and now, as I turned the final pages of The Ladies of Grace Adieu and other stories - sheer disappointment that there was no more to read. I've had such a lovely five days exploring and re-exploring, in some cases, the magical world that Susanna Clarke has built. For those of you who are unaware of this author, she made a debut a few years ago with her faerie novel, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. It is set in Regency England where magic is a highly scholarly field with only two gentlemen (the ones whose names make up the title) really practicing it. Clarke brilliantly weaves magic mixed with many real political issues of the day, especially the battles with Napoleon Bonaparte. Clarke recreates the original meaning of 'faerie'. It isn't happy and pleasant; it is eerie and unnerving sometimes. It's the kind of stuff country folk must've talked about in fearful and hushed tones when the moon was up and they gathered round the warm fires of their humble homes. The kind that they used most effectively to describe strange things that happened around them that they could not otherwise explain.We see this world again in Clarke's book of eight short stories. While all of them have something of the fae in their stories, whether in great amounts or small, they are each of them so different from the others - with completely different plots and protagonists that are so unalike.

“The Ladies of Grace Adieu“

This one is about three young ladies who prove to be practicing magicians. However, in Regency England, it is believed that only men can do magic, and for the most part there are only two, at the time, who actually practice magic – Mr Norrell and Jonathan Strange of the Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell fame. But these women are quite content to have things as they are, delighting and scorning the ignorance of men and their opinions of the female sex. If you’ve read Clarke’s enormous novel you will find that the men magicians tend to argue a great deal over theories and give absolutely no importance to what is known as Faerie. On the other hand, the women magicians are firm believers in Faerie and the potent magic of Faerie…hence their magic is also of a different sort. (You will find this difference, not only in this story but in all the stories that involved magic by women.)

Now, one of these ladies is a governess to two orphan girls who are to come into a great deal of inheritance when they leave behind their minor status. An uncle of theirs (also their trustee) comes over one day with the intent of doing away with the children so that he might inherit everything. The governess and her two friends do all in their power to prevent any harm from coming to the children.

“On Lickerish Hill”

Now this story is sort of a spin-off or rather, an adaptation of the well-known tale of “Rumplestiltskin“. The story is told in the first person by a young woman who seems to be rather low down the rung of society. Due to a lie her mother tells a rich landlord, Miranda (the narrator) finds herself married to him. In the last month of their one year of being married he locks her in a tower and tells her to spin the finest silk off flax. And the rest is history with a slight twist – it is actually quite dark in terms of atmosphere, though the tone is a bit light due to the rather practical cheerfulness of the narrator herself. She is no weepy, moany woman. She is constantly on the go (not physically speaking), figuring out her next move. It is interesting, however, that many things seem to turn out because she seems to have planned it that way. However, one does not really see her planning anything. At the end I wondered if she just got lucky. But really…you can’t say with Miranda.

“Mrs Mabb”

I think this tale was so typically faerie. Have you ever heard of fairy folk tales from the British Isles where people suddenly disappear, see strange things, grow old over night, etc etc? Well, this could be one. A young woman called Venetia comes back to her little village, from attending to a friend who was extremely ill, to find that a neighbour has got her claws into the man Venetia was hoping to marry. Convinced that Captain Fox really loved her, Venetia seeks Mrs Mabb. But the latter is a mystery and like the elfen fires one hears of in the woods, Mrs Mabb’s location keeps changing and strange keep happening to our heroine, until, at long last, the Fae gives her back her Captain.

"The Duke of Wellington Misplaces His Horse"

Yep! This is about the Duke. And this story is set in the world of Neil Gaiman's Stardust. More specifically it is set in the town of Wall. Wellington isn't particularly popular among the inhabitants of Wall when he comes to visit him, and one of them plays a trick on him. As a result his horse strays onto the faerie side of Wall, and when Wellington goes to get him back he comes across a strange stone house with a beautifully lady busy at embroidery. This is a very short piece, and one of two in this collection that portrays the power the women have with their needle skills.

"Mr Simonelli or The Fairy Widower"

Simonelli is a poor scholar and priest who is encouraged to accept a living in a 'rich' parish. On his arrival he finds himself assisting with a strage delivery in which the mother dies in child birth, and meets some very strange people. John Hollyshoes claims to be the master of All-Hope (the little village). But Mrs Gathercole, the acting patron of the village, has never heard of Hollyshoes. Hers is the only rich establishment in an otherwise extremely poor village. Simonelli journals his entire experience in this little village, as well as the discovery of who he really is. This entire story is told in the form of journal entries.

"Tom Brightwind or How the Fairy Bridge was Built at Thoresby"

David Montefiore is a Jewish doctor who has been called to attend to a sick man on his death bed. One of his closest friends, Tom Brightwind who is a fairy prince, declares his intention on accompanying the doctor. On their way there they come to an astonishingly poor village called Thoresby. The squire has been negligent in his duties, allowing the village to go to ruin for lack of a bridge over the river that separates it from the more commercialised land. Brightwind decides to take a hand as a whim, and overnight he builds a fairy bridge, and spawns yet another son in the process.

"Antickes and Frets"

This is a very short piece that deals with Mary Queen of Scots when she was Queen Elizabeth's prisoner. She seeks to kill her cousin in the hopes that she might inherit the throne of England. But the Countess in charge of her is just too clever. Again, this is a story of magic through embroidery. Apparently, antickes and frets refer to two kinds of embroidery used in Elizabethan tapestry.

"John Uskglass and the Cumbrian Charcoal Burner"

John Uskglass is the Raven King of North England, the lord of Faeries and the most powerful magician in the kingdom. On one of his hunting sprees he stumbles across a charcoal burner and destroys this man's only possessions. Angry and upset, the charcoal burner prays to the saints, and revenge is his. Uskglass returns, thinking the charcoal burner is a brilliant magician. He offends the old man again, and again the man cries out to the saints and he is avenged. This whole goes another round until finally Uskglass accepts defeat.

Apparently, this story is supposed to be a retelling of a tale, much like "On Lickerish Hill" (the second story reviewed in this collection). I am not sure if this is a re-telling as the previous sentence means it, or if it is a re-telling within Clarke's magical universe. I say this, because I haven't heard of any story that moves along these lines. If you have please do tell me, I'd love to have a read!

So, there it is! The eight stories in Susanna Clarke's Ladies of Grace Adieu and other stories. This was an incredibly enjoyable read and I would recommend this collection to anyone who loves fantasy, history, literary fiction, Jane Austen and fantastic writing!

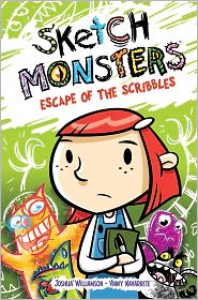

Mandy is an eight-year old who has trouble expressing her emotions, no matter if circumstances are happy, joyful, sad or painful. The day Mandy's sister leaves home for higher studies, she gives Mandy a sketch book. No sooner does her sister leave than the little girl heads over to her favourite spot and sketches a whole lot of monsters. Later, in the night, Mandy finds that her monsters are missing. What happens next is this little girl's journey to learning how to express whatever she feels without any inhibitions. The story-teller, Joshua Williamson, wants to let children know that it is okay to feel happiness, joy, anger, fear and pain. These emotions are what make a person whole and complete. The little Mandy at the end of the story is so completely different from the Mandy of the beginning.

Mandy is an eight-year old who has trouble expressing her emotions, no matter if circumstances are happy, joyful, sad or painful. The day Mandy's sister leaves home for higher studies, she gives Mandy a sketch book. No sooner does her sister leave than the little girl heads over to her favourite spot and sketches a whole lot of monsters. Later, in the night, Mandy finds that her monsters are missing. What happens next is this little girl's journey to learning how to express whatever she feels without any inhibitions. The story-teller, Joshua Williamson, wants to let children know that it is okay to feel happiness, joy, anger, fear and pain. These emotions are what make a person whole and complete. The little Mandy at the end of the story is so completely different from the Mandy of the beginning. The drawings by Vicente Navarrete, are absolutely perfect for children between the ages of 7 and 10. The monsters look exactly like something a child would draw in his/her sketch book, and none of them are terrifying in any way. I have to admit that I'd wondered how the 'angry' monster would work out. But he was just as loveable and amusing as the rest.

I really enjoyed reading this little book. The story is so simply told. The colours are so vibrant. And Mandy should be easy for children to identify themselves with.

After the story, in the final few pages, is brief peek at how the sketches have been worked out, and a little puzzle or two for the children answer.

I wasn’t quite sure what to expect when I picked up Northanger Abbey. Austen’s charm I was expecting, of course, but I wasn’t sure what her spoof was going be like. I began reading, and I must admit, for the first half of this very short novel I’d completely forgotten that it was supposed to be Gothic in scope. However, it is clear right from the start that Austen was working with an anti-heroine. Of course, while such heroines we find in plenty these days, I’m sure, at the time Austen wrote, beauty and various accomplishments were the standard requirements of a heroine. One only needs to read the Grimm Brothers and Hans Christian Anderson to know how true this is. But, right at the start, we are introduced to a young Catherine who is an absolute ‘plain Jane’ and a tom boy to boot. She has no accomplishments whatsoever, and does not seem to be in the least interested in acquiring any. She is content with who and what she is, and later loses herself in volumes of romances that her parents wonder are perhaps not good for her.

I wasn’t quite sure what to expect when I picked up Northanger Abbey. Austen’s charm I was expecting, of course, but I wasn’t sure what her spoof was going be like. I began reading, and I must admit, for the first half of this very short novel I’d completely forgotten that it was supposed to be Gothic in scope. However, it is clear right from the start that Austen was working with an anti-heroine. Of course, while such heroines we find in plenty these days, I’m sure, at the time Austen wrote, beauty and various accomplishments were the standard requirements of a heroine. One only needs to read the Grimm Brothers and Hans Christian Anderson to know how true this is. But, right at the start, we are introduced to a young Catherine who is an absolute ‘plain Jane’ and a tom boy to boot. She has no accomplishments whatsoever, and does not seem to be in the least interested in acquiring any. She is content with who and what she is, and later loses herself in volumes of romances that her parents wonder are perhaps not good for her.We see the effects of all her novel-reading when she sets off with her kind neighbours, the Allens, to seek her fortune (in the heroic sense of the term though she has no such thought in her head) in the society of Bath. She meets with a couple of families there, one of which provides the hero to the story. Harry Tilney is unlike the usual romantic hero. He reads novels, finds them entertaining, loves to laugh and goof about, and has no dark or gloomy or brooding past. The Gothic-ness of the novel begins when the Tilneys invite Catherine, half way through the novel, to come over to their home for a stay. She discovers that they live in an abbey and she is simply delighted, immediately thinking of all the ghoulish adventures open to her.

At the end, with no real adventure to find her, Catherine lets all her knowledge from the books she has read to come to play on her “sensibilities”. She finds a mysterious, ‘hidden’ cabinet in her room with a roll of papers secreted away in a hidden compartment, she ‘discovers’ that the master of the house (General Tilney) is loath to open up the rooms of his dead wife to Catherine which immediately leads her to suspect that perhaps his wife is not dead at all but is a prisoner within those ancient rooms, she ‘experiences’ the tell-tale weather of all Gothic romances, and generally sends herself into near hysteria with all her imaginings. Later, of course, she is made to see the error of her ways and is quite embarrassed to find that she was carried away by all her reading.

I simply enjoyed the way Austen wrote this entire spoof. It was charming and witty, and I don’t think I’ve ever chuckled so much while reading any of her other books. Right from the beginning to the end of Northanger Abbey I was well and truly entertained. There is mention of a great many books and writers in this novel (I’ve never seen so much mention of her literary contemporaries or fore-bearers, actually, hardly any, in her other novels), and I was soon under the impression that most of the spoofing was based off Anne Radcliffe‘s books – the one that gets mentioned most often and is our heroine’s favourite is The Mysteries of Udolpho. However, I did not get the impression that Austen despised the Gothic genre. In fact, she seemed to be a fan of Mrs Radcliffe, who was just amusing herself with gently poking fun at what she admired.

Northanger Abbey, is very different from the other Austen novels I’ve read (I’ve read all except Mansfield Park and Lady Susan). Besides its aim at being a spoof, it lacks the maturity of her other novels – not just in terms of style and her wit, which becomes more subtle and thereby sharp, but also in terms of the themes she deals with in her later books (yes, Northanger Abbey was meant to have been published in 1803…eight years before Sense and Sensibility, her first published work).

There are some who claim that reading Mrs Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho would help us to better understand and appreciate Northanger Abbey. But personally, I feel, that if you’ve ready even one or two Gothic novels from any era, you are bound to understand this novel really well. While I have yet to read Mrs Radcliffe, I have read the likes of Jane Eyre, Dracula, a couple of Victoria Holt books (all of them are Gothic) and have watched a couple of versions of Rebecca; and knowing these was enough for me to understand all the Gothic elements that Austen gently mocks at in her novel.

I finished Gone with the Wind this weekend. There is still a part of me that wishes I had prolonged the last few chapters, given myself time to savour the final pages of this indescribable epic. It is such a powerful story of magnificent proportions in terms, not only of story, but of background, setting, and characterization. Seriously, I think Mitchell has a gift for drawing out her characters with such subtle complexity. As Mel says in his review of the same – The characters were amazingly well developed. Just as soon as you think you have a character all figured out they do something that shocks you but you realize it is right in character and you just did not understand them well enough.

I finished Gone with the Wind this weekend. There is still a part of me that wishes I had prolonged the last few chapters, given myself time to savour the final pages of this indescribable epic. It is such a powerful story of magnificent proportions in terms, not only of story, but of background, setting, and characterization. Seriously, I think Mitchell has a gift for drawing out her characters with such subtle complexity. As Mel says in his review of the same – The characters were amazingly well developed. Just as soon as you think you have a character all figured out they do something that shocks you but you realize it is right in character and you just did not understand them well enough. Naturally, the most incredibly fascinating of all her characters is Scarlett O’Hara. I hated her. I was fascinated by her. I admired her. I despised her. Oh, and definitely at the end I admired her all over again. I can’t say that at any point I loved her or even liked her much. But I admired her traits of common sense although I did not agree with the means through which she worked for her gains. And, of course, the strength she has to survive and help all those, who depend on her strength, to survive as well.

The rest of this post is full of spoilers since it is mainly an analysis of sorts. I've left the labels open and the rest is for those eyes that have already read the novel, and/or for the curious. :D

The “destruction” and “reconstruction” of Scarlett

Right from the start we see glimpses of a Scarlett we cannot much like. We see how she cannot stand it when any of her beau are attracted to her contemporaries. We also see how she “steals” them away with her whiles and charms. We see a determined young woman (I refrain from saying ‘lady’) who is used to getting her way and knows exactly how to get what she wants. She is like a spoilt child, and there is so little of the woman in her, really. As the story moves on we begin to be aware of her instincts of a survivor. She is strong, so much so, that the only person who truly knows and understands her, Rhett Butler, leaves her alone with four helpless dependents to find their way back to Tara. He knows that she will make it home without getting into danger. As a result we find that Scarlett has no use and spares not pity for the weak. This would explain the utter contempt she feels for Melanie, and later admiration when the latter shows that her spirit is strong even if her body is weak. And yet, considering that she despises weakness in others, she cannot understand that Ashley stands for the kind of weakness she has no patience with. She is so completely obsessed with him that it is too late by the time she realises that the two people she really loves are the two people she has shunned from the start – Melanie and Rhett. Then there is her obsession with money. Her greatest fear is such a basic one and such an earthy one that her drive to never be hungry again causes her so much in terms of the things that truly matter. At the end, though, when she realises that she loves Rhett Butler, she even understands that if they were poor it would not really matter as long as she had love.

I believe all this realisation and loss begins the process of her growing from a willful child to a determined woman. Strange, though, isn’t it, that this process begins only toward the end of the novel, not to mention, that in spite of all the trials she goes through up to that point she can still maintain the cruel ignorance of a child. Personally, I like how this entire process of her personality parallels that of the “destruction” of Georgia and the “reconstruction” of the same. In the last page we see that Scarlett is not broken but is as determined as ever to get her way. One can only hope that this time around she would go about it in a more mature manner.

Character foils for Scarlett

I suspect that Mitchell set up almost every character beside that of Scarlett’s. The three other main characters are Melanie, Ashley and Rhett. It is quite ironic that the two of these three characters Scarlett has the most in common with, she hates, while she loves Ashley without really understanding or knowing him. Melanie and Scarlett are both survivors. They are both strong in spirit, though Melanie lack physical strength. However, the strong fighting spirits are quite different. Scarlett fights with a will to come up on top, to never be hungry or without money again. Her driving force centres about herself. On the other hand, Melanie’s strength is for others. They lean on her and see her as a beacon of light – Ashely, the genteel people of Atlanta, the riff-raff of the same, and quite surprisingly Rhett Butler himself. Of course, Scarlett depends on her a great deal too. Something she realises only when she loses Melanie. If only Scarlett had recognised that the true strength of Melanie was what Scarlett herself understood only as a weakness. Up against Melanie, we see that Scarlett could have survived without losing her soul if only her aim had not been money.

Rhett Butler also serves as a foil to Scarlett. He is also there to show us how much of herself Scarlett destroys in order to never be hungry again. While these two characters are so completely alike in being selfish and unscrupulous in their means, we find that Rhett is still humane. He knows what kind of person he is. He knows the truth about himself. And so, while he laughs at the world he jeers at himself too. He is a cynical man. But he recognises what kind of people he comes across. He realises that Melanie is truly “a great lady” and not hypocrite hiding behind social etiquette. He knows why Ashley cannot survive in the world after the Civil War. Seeing what Rhett is one cannot help but notice that Scarlett is completely devoid of introspection. She is shrewd, smart, but as ignorant as a selfish child. Everything she sees and understands revolve around her insignificant self and so she never realises the worth of the people who are closest to her.

Ashley Wilkes is the one Scarlett has the least in common with. In fact, apart from their background they share nothing else except delusion. They are both so deluded about the other, each thinking that they know the other so well. I found it so frustrating when both of them said things that took for granted that they each understood the other. Even at the end, when Scarlett realises that Ashley is as much a child as she is, and is way more lost than she has ever been, she does not truly understand why this is so.

Ashley, a whimp?

He’s only a gentleman caught in a world he doesn’t belong in, trying to make a poor best of it by the rules of the world that’s gone. (p.1015)

This is how Rhett describes Ashley to Scarlett when she finds that the latter is not what she had thought him to be. Do I believe Ashley is a whimp? I doubt it. We only say so in comparison to Rhett. But we know that he is indeed noble, honourable and full of physical courage. As he tells Scarlett when she says she fears hunger, he does not fear starvation. What he really fears is living in a world that he does not know, a world that is far removed from the libraries of home. He is, by nature, a gentle man – a man brought up in times of leisure, who lives in dreams, in the writings of the past, in all things that are beautiful, that is art. With the war Ashley has lost his “mainspring”. I love the speech that a minor character, Will Benteen, gives at the funeral of Gerald O’Hara:

Everybody’s mainspring is different. And I want to say this – folks whose mainsprings are busted are better dead. There ain’t no place for them these days, and they’re happier bein’ dead… (p.704)

I think Ashley’s mainspring was Georgia of the past. With it went his will to survive. He was afraid of living. He did not know how he was to live in a world he was not brought up in. I believe those who survived the war, in the real sense, were those who loved a good challenge. The kind of people who perk when something dares them. One has only to look at the aristocrat Rene, and his lame friend, Tommy – both of who obviously reveled in the challenge to remake their lives. And then the determination of others, like Mrs Merriweather, who refused to let anything defeat them. For those like her they were still fighting a war that they had to win. But Ashely had never believed in this war. All he longed for was the past. And he was not alone in his longing.

Everything in their old world had changed but the old forms. The old usages went on, must go on, for the forms were all that were left to them. They were holding tightly to the things they knew best and loved best in the old days, the leisured manners, the courtesy, the pleasant casualness in human contacts and, most of all, the protecting attitude of the men toward their women. (p.598)

Ashley simply didn’t have the heart to fight because he never had wanted to fight. Ashley, we see, isn’t a doer. He is a dreamer, and so completely misplaced. I doubt, though, that that gives anyone call to say that he is a weakling or a whimp.

Ashley and Rhett

Strangely, whenever I came across either character I never thought of their differences but their similiarities. It’s quite amazing how much these two, seemingly different men, actually have in common. As Rhett says (or was it Ashley who did? I cannot recall), fundamentally both men are alike. They come from similar backgrounds and upbringing, even to the extent of their bookish knowledge. Both of them strongly believe that the war is useless, that no good but loss of lives and a way of living can come out of the war. We see how it is the two of them that work to stop the Klan from functioning. And really, it is not ironical. Both are aware of the concept of the “winnowing of the weak”. In fact, both of them, at different times tell Scarlett this using almost the same words. Both of them are very self-aware. They have no illusions about themselves. Ashley is aware that he is not made of the mettle needed to survive the aftermath of the war, and he understands why. Rhett knows himself to be unscrupulous and self-centred.

Melanie

It strikes me as interesting that Melanie is what Ellen O’Hara, Scarlett’s mother, would have been had she survived the war. The person Scarlett most admired and loved was her mother, and yet she was as unlike her mother as night is to day. It comes to mind how often Scarlett thinks of her mother’s teachings only to put them aside saying, none of it makes sense if she and her dependents are not to starve. Yet Melanie retains her gentleness and kindness in the midst of strife, while growing in strength and offering it to others. Really, I think Melanie is the strongest character in the story. She is the pillar of strength where Ashley, Scarlett and Rhett and even Atlanta, are concerned. It is she who boosts up the morale of all the other characters.

Melanie and Rhett

I like the similarity between these two characters. I like how each of them is strength behind their deluded halves. How they are both the reason Ashley and Scarlett, respectively, make it through as far as the end of the novel, and how the latter two realise this only once they have both lost Melanie and Rhett, respectively. I also love the relationship these two have with each other – one of mutual respect and kindly love.

Mitchell’s mouthpieces

I noticed how Mitchell uses certain characters to voice insights into others and the real, underlying situation in Georgia’s Southern society. Among these characters Mitchell uses, rather prominently, Ashley and Rhett. They are both observers of the world around them and constantly seek to enlighten Scarlett, and there-by the reader about people, their situations and their motives. Quite often, in fact, Rhett serves as an analyser of Scarlett’s nature. Another character who plays an interesting part in the revelation of insights into peoples’ nature is Old Mrs Fontaine. While she does tend to miss the mark where Scarlett is concerned (really, I believe Rhett is the only one knows her) she is spot on with every other character including, and especially, Ashley Wilkes and Melanie.

Mitchell’s thoughts?

I do not presume to know what Mitchell was thinking as she wrote this story, but it seems to me that Mitchell is just as admiring and despising of Scarlett as most readers are bound to feel. I doubt she particularly likes Scarlett. You can see how much she jeers at her own character even to describing her as having a “shrewd shallow brain” – an absolutely apt description, I think. It also seems to me that Rhett is really Mitchell, or in other words, Mitchell uses Rhett as the portrayer of her feelings regarding, not only Scarlett, but society and its strange sense of honour and dignity when pitted against common sense. And yet, it would seem, in spite of herself, even as Rhett does, that she cannot help but admire this society and admire the strength that is Scarlett’s. Perhaps, even in spite of Scarlett, Mitchell loves her as does Rhett.

However, from what I’ve heard, Mitchell’s true heroine is really Melanie. I think this becomes quite apparent when Melanie dies as we see who this affects all the people around her including the other main characters. All of them realise that she was their foundation, in a manner of speaking – the person they depended on for love and kindness and generosity. I think Mitchell also sets Melanie up against Scarlett in showing us how, in order to survive, one need not lose one’s humaneness and natural courtesy. Yet, now that I think about it, I wonder, if, in order for Melanie to retain her gentle nature and survive if she did not need Scarlett a great deal in her turn. I think that might be true or Melanie could not have survived – physically that is.

And there you have it...my thoughts on Gone with the Wind. :)

This one is adorable! I wonder if it would make my little one excited to go to sleep by the end of it? Or would he just drift off while I’m only in the middle of this happy tale of the world saying good night and falling asleep? I find all the strange little creatures of Seuss' imagination so cuddly and imaginative! Not to mention that the illustration helps us understand his creatures better.

This one is adorable! I wonder if it would make my little one excited to go to sleep by the end of it? Or would he just drift off while I’m only in the middle of this happy tale of the world saying good night and falling asleep? I find all the strange little creatures of Seuss' imagination so cuddly and imaginative! Not to mention that the illustration helps us understand his creatures better. My husband read this book ahead of me and he was in stitches. He’d never read anything like this before, and one has to admit, it’s quite amusing!

At the fork of a road

In the Vale of Va-Vode

Five foot-weary salesmen have laid down their load.

All day they’ve raced round in the heat, at top speeds,

Unsuccessfully trying to sell Zizzer-Zoof Seeds

Which nobody wants because nobody needs.

Tomorrow will come. They’ll go back to their chore.

They’ll start on the road, Zizzer-Zoofing once more

But tonight they’ve forgotten their feet are so sore.

And that’s what the wonderful night time is for.

Ever since I learnt of Dr Seuss, Horton has been a favourite character of mine. He is so innocent and full of good intentions, and he sticks to his guns no matter what! I was simply thrilled when Horton Hears a Who came out as a movie (I’d never read the book until now), and I quite fell in love with it. I finally got the book (as you can see), and though I see how different the movie is from the original, I love them both just as much!

Ever since I learnt of Dr Seuss, Horton has been a favourite character of mine. He is so innocent and full of good intentions, and he sticks to his guns no matter what! I was simply thrilled when Horton Hears a Who came out as a movie (I’d never read the book until now), and I quite fell in love with it. I finally got the book (as you can see), and though I see how different the movie is from the original, I love them both just as much!I think this book is a nice story to tell a child. There’s so much a child can learn from it without being preached at.

A person’s a person no matter how small.

Horton’s loyalty is also so touching. And one cannot forget the expressive illustrations! I just can’t wait to start reading this to my son!

The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus

It had been about eight or nine years since I had last read Christopher Marlowe's Dr Faustus. I recall how I had had to study it on my own for I had been ill when my professor dealt with it in my undergraduate class. I also recall how much I loved, how it left me passion-spent, sitting at the edge of my chair as Faustus steadily moved toward eternal damnation.

It had been about eight or nine years since I had last read Christopher Marlowe's Dr Faustus. I recall how I had had to study it on my own for I had been ill when my professor dealt with it in my undergraduate class. I also recall how much I loved, how it left me passion-spent, sitting at the edge of my chair as Faustus steadily moved toward eternal damnation.A year later, while doing my masters, another professor asked us to do a short assignment on Marlowe. I had read of how, during his time Marlowe was considered an atheist. I still find it hard to understand why. Was he an atheist because he dared to be a 'freethinker'? That would be undrestandable, considering the power of the Church during the Renaissance, and their dislike of anything that went against what the Church fed the common people. So, if this be the case, then I am not confused.

What do I mean?

Dr Faustus is an incredibly passionate and powerful piece of work. It is all about a man who sells his soul to the devil for knowledge and power. While the story itself is based on a German history, the language, the ideas, the passion and conviction behind the words are so unmistakably un-atheist like. Throughout the play Faustus is plagued by the wrongness of what he has done. Yet Mephistophilis, one of the Devil's main agents, always wins over the words of the 'good angel', and we see Faustus digging his whole faster and deeper.

The irony of the deal struck with the devil

"When Mephistophilis shall stand by me, What god can hurt thee, Faustus? thou art safe Cast no more doubts.--Come, Mephistophilis, And bring glad tidings from great Lucifer;-- Is't not midnight?--come, Mephistophilis, Veni, veni, Mephistophile!" Marlowe, Christopher. The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus (Kindle Locations 228-230). manybooks.net.

In his bid to justify what he has done, Faustus, ironically and tragically places his trust in the one creature he should fear, believe himself safe from God. Yet, ambition and the thirst for knowledge are the real things that compel his continual foray into the occult. He seeks to enslave evil spirits, to make them do his every bidding:

"But, tell me, Faustus, shall I have thy soul? And I will be thy slave, and wait on thee, And give thee more than thou hast wit to ask." ibid (Kindle Locations 236-237)

Yet, who is really master? Faustus or Mephistophilis? Would Faustus be given all that he asks for? Yet the devil gets the better end of the bargain. However, the deal does not stop here. The 'good angel' and the 'bad angel' constantly make their appearance as Faustus' conscience. Right up to the very end he is pricked by doubt and shame.

The real tragedy

But the real tragedy is when he cannot bring himself to repent, for he cannot believe God would forgive him so much evil. It begins with his lust for power over the domain of the spirits, that leads him to strike a deal with the devil, pledging his soul for twenty-four years of knowledge and power. Once this is done we see the immediate deterioration of all things held sacred. Faustus wants a wife. But his 'slave' says marriage is of no consequence, he might have beautiful courtesans and other lovely women every day. Then comes his constant tryst with evil spirits, the ultimate being when he has physical intercourse with one disguised in the form of the fair Helene of Troy - "Was this the face that launch'd a thousand ships, And burnt the topless towers of Ilium-- Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss."-- ibid (Kindle Locations 530-531)

Come the last hour of his freedom, and the agony he suffers is great. I find that last scene the most beautiful and nerve-wracking scene of the play. Faustus longs for the peace of forgiveness, mercy and salvation, but he cannot bring himself to believe that he can be forgiven. The last words he utters as the clock strikes the end is both pitiful and horrifying at the same time:

"O, it strikes, it strikes! Now, body, turn to air, Or Lucifer will bear thee quick to hell! O soul, be chang'd into little water-drops, And fall into the ocean, ne'er be found!" ibid (Kindle Locations 576-577). manybooks.net.

In the footnote of my kindle version, is given a very gory description of Faustus' remains as written in The History of Doctor Faustus. One can only imagine the gruesome torture of his dying.